Haifa

Today, the city of Haifa sits on what is known as “Israel,” an occupied territory which used to be Palestine. This narrative will not discuss the post-1948 occupation which led to the exile and displacement of millions of Palestinians, but rather the richness of pre-1948.

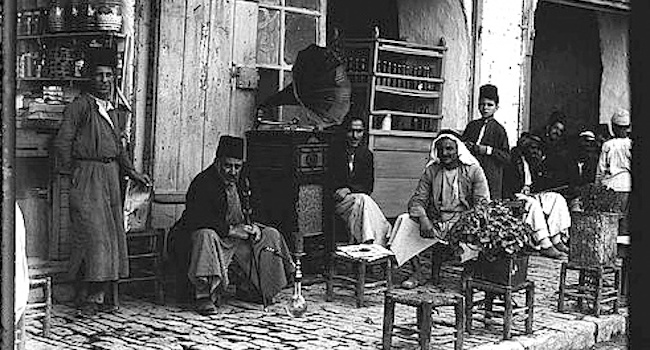

In Haifa, bars and cafes served as collective and meeting spots for the youth, political activists, sectarian groups (Muslim and Christian), playing cards, smoking argile (or hookah), or a place to drink alcohol. To address the cultural curiosity, some of these cafes did not serve alcohol while others permitted it. Today, Haifa’s cafes are merely a buried memory laying under newly renovated infrastructures and the streets renamed in Hebrew. This is just a fraction of the colonization and occupation of this historic Arab land.

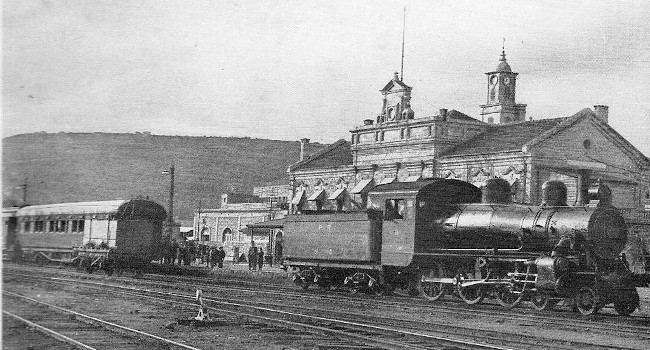

Haifa was established in 1761 by the Ottoman governor Daher Al-Omar Al-Zidani, who aimed to

protect a small fishermen village from pirate attacks. Haifa lies in a strategic location,

at the nexus of trading routes from Syria and the Arabian Peninsula as well as the

Ottoman Hijazi railway (Mansour, 2006). The British mandate established in 1933 a

modern port in Haifa to transfer petrol from Iraq. These projects contributed to Haifa’s

economic and social growth and increased immigration of Palestinians from nearby towns in search

of employment. Nevertheless, also Jewish immigration raised rapidly, from 25% Jews of

Haifa’s residents in 1922 to about 50% in 1947 (Seikaly, 2002). The Jewish immigrants

established separated new neighborhoods. These neighborhoods where portrayed as modern,

unlike the Palestinian spaces, thus echoing Haifa vision in Herzl's (the founder of the modern

political Zionism) book Altneuland; A modern and clean city, in the spirit of the cities of Europe.

Such discourse was used in formal and informal forums to justify the Zionist colonial agenda to

control Haifa (Seikaly, 2002; Kolodney & Kallus, 2008:341).

In the aftermath of the 1948 war – the Nakba, about 95% of the Palestinian residents of Haifa

became refugees. Their properties were controlled by the state of Israel which rented,

demolished or sold it (Fischbach, 2003). Although, this move was in direct contrast to the

Palestinian refugees’ constitutional right to property and the international humanitarian law

(Bishara, 2009). The elimination of the Palestinian city continued in the following years after the

establishment of Israel; the streets names were Hebrized and most of the Old City was

demolished. Evidently such plans aimed to ‘urbicide’ the Palestinian city, namely, erasing the

existing Palestinian landscape and replacing it with a new spatial order, knowledge and identity

(Kolodney & Kallus, 2008:332, Ben-Arie, 2016:186). Ironically, on the Old City buildings’ debris

the district courts of justice - law building was built in the 1980s. Such destruction is continuing

today through neoliberal urban planning projects, such as the “artists’ quarter” plans taking

place in Wadi Al-Salib (Sa’di-Ibraheem, 2020).

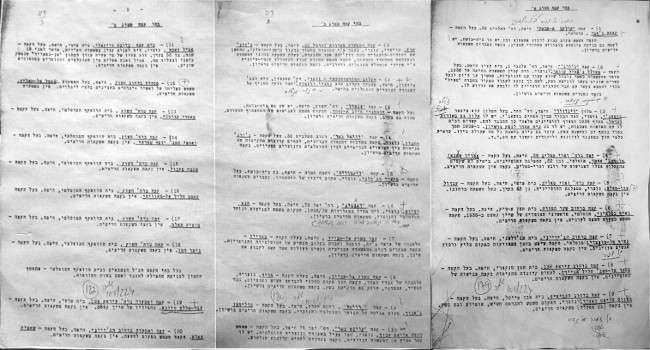

Contemporary sources testify to the vibrant economic social and cultural life of the city, which

included the production of several newspapers, social organizations, several markets, religious

institutions, political movements and workers’ groups. Some of the documentations can be

found in Israeli archives, such as the documents –discussed here - the Hagana espionage on

Palestinian coffee shops in the 1940s. Yet, following the insights of the considerable literature

on colonization and archives, such colonial sources must be approached critically, not only

towards the validity of the content but also towards the narrative, discourse and categorization

used in it.

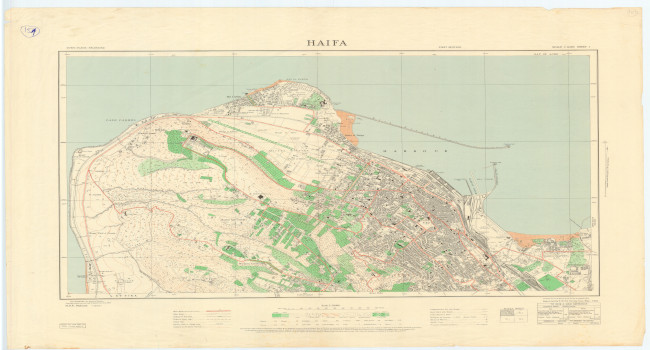

The Map!

References

- Ben-Arie, R. (2016). The Haifa Urban Destruction Machine. In Frichot, H., Gabrielsson, C., & Metzger, J. (ed.), Deleuze and the City. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 178-192.

- Bishara, S. (2009). From Plunder to Plunder: Israel and the Property of the Palestinian Refugees. Adalah’s Newsletter, volume 64. Retrieved from: https://www.adalah.org/uploads/oldfiles/features/land/Suhad_Plunder_English_edited_30.9.09%5b1%5d%5b1%5d.pdf

- Fischbach, M. R. (2003). Records of dispossession: Palestinian refugee property and the Arab-Israeli conflict. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kolodney, Z., & Kallus, R. (2008). From colonial to national landscape: producing Haifa’s cityscape. Planning Perspectives, 23(3): 323-348.

- Mansour, J. (2006). The Hijaz-Palestine Railway and the Development of Haifa. Jerusalem quarterly, (28).

- Mansour, J. (1989). Haifa Arab Streets. New edition 1999.

- Mansour, J. (2007). Haifa Arab Tours.

- Sa’di-Ibraheem, Y. (2020). Privatizing the production of settler-colonial landscapes: ‘Authenticity’ and imaginative geography in Wadi Al-Salib, Haifa. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. Advanced online publication: http://doi.org.1177/2399564420946757.

- Seikaly, M. (2002). Haifa: Transformation of an Arab society 1918-1939. IB Tauris.